Going against the grain isn’t easy—especially in a world where brands are constantly trying to one-up each other. Here are four examples of companies that completely zigged when others zagged and the consequences that followed.

REI

For many brands, Black Friday (or what now seems like Black November) is a yearly sales pinnacle. So, when REI announced that it was closing its doors on Black Friday last year, the outdoor retailer made headlines.

“I think it’s important for brands to always be true to who they are,” Jerry Stritzke, president and CEO of REI, told CBS This Morning at the time. “And for us, encouraging people to get outside, particularly on a holiday like Thanksgiving, we do believe that is an important message.”

REI dubbed the initiative #OptOutside, and it paid its employees to not work on the shopping holiday. The company created a campaign website that featured recommended hiking trails and encouraged people to share their outdoor adventures on social media. And while the brand had a “black takeover screen” on its website urging people to head outdoors, an REI spokesperson told GeekWire that customers could still view products and make online purchases; however, the orders wouldn’t be processed until the next day.

According to a 2015 REI press release, more than 150 companies, nonprofits, and agencies joined the retailer in supporting people to spend Black Friday outdoors, prompting “nearly one million endorsements for OptOutside.” GeekWire also cited data from web and app analytics company SimilarWeb claiming that REI.com experienced a 10% lift in traffic on Thanksgiving and a 26% increase on Black Friday.

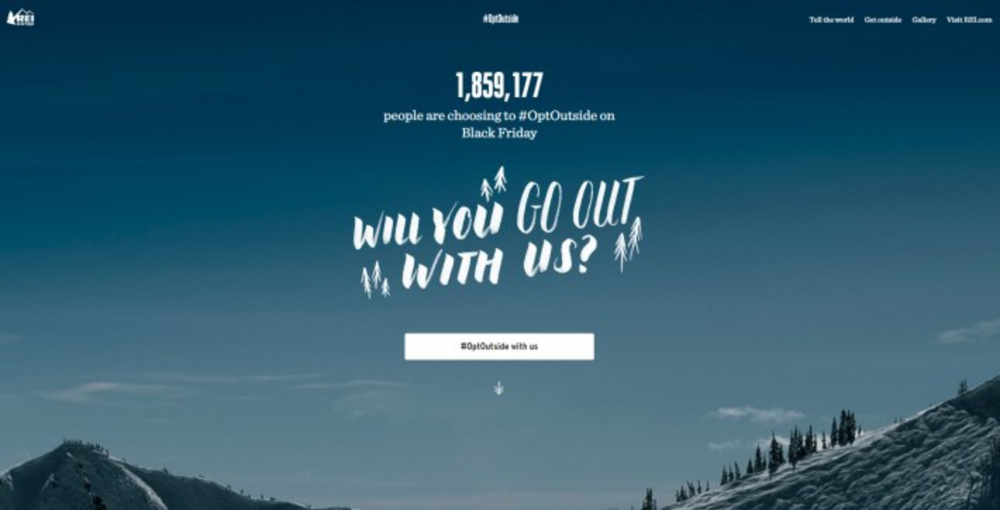

The campaign was such a success that REI is inviting people to #OptOutside again this year. According to a recent REI press release, more than 1.8 million people have stated their intent to spend Black Friday outdoors this year, and 475 companies, nonprofits, and public sectors have pledged to help people spend more time outdoors this season. In fact, many state parks are waiving fees on Black Friday.

As Stritzke suggested on CBS This Morning a year ago, REI’s move emphasizes the importance of brand authenticity. In today’s crowded environment (which is even more jam-packed on Black Friday), it’s the brands that stay true to their values and practice what they preach that resonate with consumers.

Southwest Airlines

Checked bag fees, in-flight meal and entertainment costs, flight change penalties: This list of add-on airline expenses can become so costly that it actually dampens travelers’ experiences. To stay true to its identity as a “low-fare” carrier, Southwest Airlines abandons many of these time-honored traditions by offering customers two free checked bags; free, in-flight, live TV; and no flight-change fees (although, customers have to pay the difference in flight costs). The airline cheekily refers to this customer service approach as “Transfarency.”

“Transfarency is a unique approach to treating customers the way they expect and deserve to be treated,” Kevin Krone, Southwest’s VP of marketing and CMO, stated in a press release announcing the brand’s 2015 Transfarency campaign launch. “Being a low-fare airline is at the heart of our brand and the foundation of our business model, so we’re not going to nickel and dime our customers.”

Southwest highlights its Transfarency assets (while jabbing its competitors) through content marketing efforts, like a “Fee or Fake” online quiz and #FeesDontFly Mad Libs.

Customer service is certainly a cornerstone in Southwest’s business model, and it shows. Southwest ranks second in the low-cost carrier category in the “J.D. Power 2016 North America Airline Satisfaction Study” with a score of 789 out of 1,000 points, falling one point behind top carrier JetBlue. But is this superb service actually impacting Southwest’s bottom line? Recent earnings might suggest otherwise. According to a recent earnings release, Southwest’s net income for Q3 2016 was $388 million—a significant drop from $584 million in Q3 2015.

The bottom line: Delivering an exquisite customer experience is always important, but brands need to evaluate if they actually have the means to deliver on their promises.

CVS

How many brands would turn down $2 billion in annual revenue? That’s exactly what CVS Caremark Corp did when the pharmacy chain stopped selling tobacco products in 2014, according to The Wall Street Journal.

“While there’s never a right time to walk away from $2 billion in revenue, this was the right time,” CVS President and CEO Larry Merlo told the news outlet. “Eliminating this obstacle will allow our company to grow over the long term.”

In a 2015 press release announcing the decision, Merlo said that selling tobacco products was “inconsistent” with CVS’s purpose of promoting health and aligning itself as a health care company—a purpose that eventually manifested into the brand adopting the name CVS Health.

CVS’s bottom line took a hit: Its front-store-same-store sales fell 4% by the end of 2014 and by 5% in 2015. However, its overall net revenues continued to grow as did its same-store pharmacy sales and prescription volume. In fact, the company’s 2015 annual report revealed that CVS Pharmacy filled 21.6% of all retail prescriptions that year, causing the company to take the lead in the U.S. retail drugstore market.

But CVS’s new company positioning may soon hit another roadblock. As Forbes recently reported, CVS’s Q3 2016 earnings report projected a loss of more than 40 million retail prescriptions in 2017 due to new restricted pharmacy networks that exclude CVS Pharmacy drugstores.

Indeed, pivoting a company based on values and evolving markets (like healthcare) is a brave move, but that’s the thing with markets—they’ll always evolve again.

Facebook has grown up quite a bit since Mark Zuckerberg first founded the social network. It’s acquired behemoths like Instagram, Whatsapp, and Oculus VR (although, its reported bid for Snapchat was unsuccessful). And while these technologies all sit underneath the Facebook umbrella, Zuckerberg and his teammates have chosen to keep their experiences fairly separate.

The reasoning behind this independent structure, according to a Business Insider article, is simplicity. “Apps that do one thing, and do it really well, are the social network’s hedge against bloat and user burnout,” it reads.

The article also points out that somebody who doesn’t like WhatsApp may still enjoy Instagram—giving Facebook more opportunities to acquire data and marketshare.

So while trying to be an all-encompassing entity has been the near downfall for some, Business Insider writes, Facebook is letting its acquired apps focus on what they do best—for now.