Terror paranoia has reached fever pitch in the wake of the Paris bombings, and heads of state are calling on the same military leaders and immigration officials they have called on for decades to battle the threat. Might they be better served to enlist the aid of digital marketers?

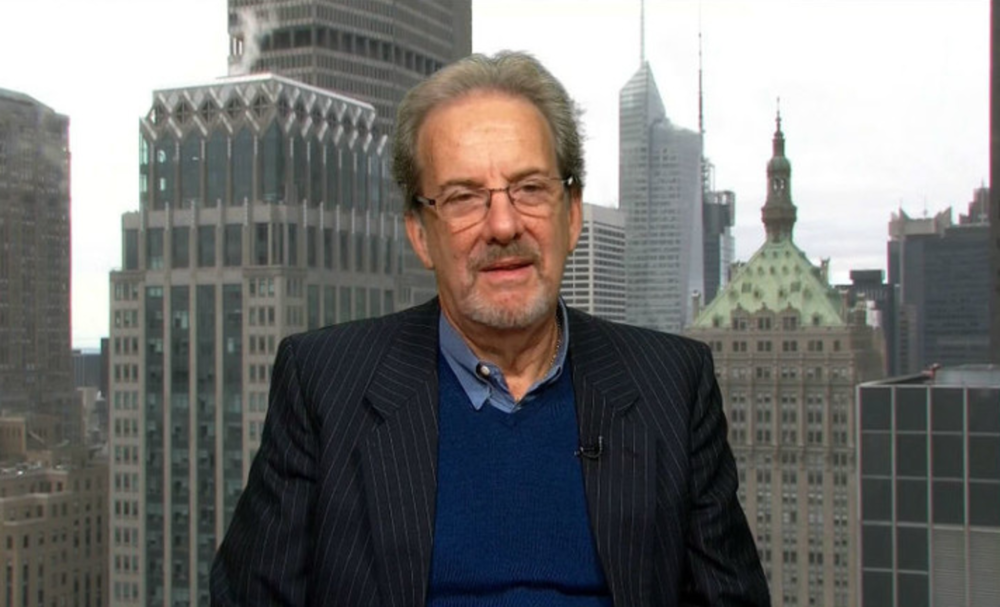

In April Scott Atran, an anthropologist who teaches at Oxford, the University of Michigan, and the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, addressed the U.N. Security Council on the topic of youth recruitment by terrorist organizations. The themes he put forth are ones that, to my mind, should be more familiar to a social media team leader than to an Air Force Colonel. Here are some excerpts from Atran’s presentation. You be the judge.

Recruits are new customers:

They knew nothing of the Quran or Hadith, or of the early caliphs Omar and Othman, but had learned of Islam from Al Qaeda and ISIS propaganda, teaching that Muslims like them were targeted for elimination unless they first eliminated the impure.

They can’t be stopped at the border, because they are converted globally:

According to “The Management of Savagery”, the manifesto of the Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia and now ISIS, a global media plan should compel youth to “fly to the regions which we manage.”

Last summer an ICM poll revealed that more than one in four French youth – of all creeds – between the ages of 18 and 24 have a favorable attitude towards ISIS; and in Barcelona just this month five of 11 captured ISIS sympathizers who planned to blow up parts of the city were recent atheist or Christian converts.

They are captured on websites and nurtured via social media:

The appeal of Al Qaeda or ISIS is not about jihadi websites, which are mostly blather and bombast, although they can be an initial attractor. It’s about what comes after. There are nearly 50,000 Twitter hashtags supporting ISIS, with an average of some 1,000 followers each. They succeed by providing opportunities for personal engagement, where people have an audience with whom they can share and refine their grievances, hope, and desires.

Young targets are open to the message:

When I hear another tired appeal to “moderate Islam,” usually from much older folk, I ask: Are you kidding? Don’t any of you have teenage children? When did “moderate” anything have wide appeal for youth yearning for adventure, glory, and significance?

Personalization is crucial:

In contrast, government digital “outreach” programs typically provide generic religious and ideological “counter-narratives,” seemingly deaf to the personal circumstances of their audiences. They cannot create the intimate social networks that dreamers need…. And any serious engagement must be attuned to individuals and their networks, not to mass marketing of repetitive messages. Young people empathize with each other; they generally don’t lecture at one another.

Still, referrals from family and friends are the gold standard:

About three out of every four people who join Al Qaeda or ISIS do so through friends, most of the rest through family or fellow travelers in search of a meaningful path in life.

If Atran is correct, and jihadism is cultivated globally among key youth segments on the Internet and not locally among indigenous Muslim populations, perhaps some readers of this website might prove more valuable to Obama, Hollande, and Cameron in their war on terror than readers of Jane’s Defence Weekly. Any volunteers?