Facebook seized the headlines this week precisely by making a play for the headlines—offering to host news and other content in return for a share of ad revenues. Some see the move as a lifeline for an ailing publishing industry. Others see it as a deal publishers may regret making.

But few have noticed just what a game-changer this could be, not just for publishing but for online marketing across the board—it potentially reduces a multi-channel environment to a handful of dominant platforms and takes the customer experience largely out of the hands of publishers.

Owning the News

The news of Facebook’s play for publishers almost overshadowed the announcements coming out of Facebook’s developer conference, F8 2015. For several months, the social giant has been talking to news organizations and other online publishers, and it is close to finalizing agreements with at least some of them to host their content inside Facebook. The New York Times, Buzzfeed, and National Geographic are the publishers named so far.

Facebook links have become almost a lifeline for news sites, driving vast quantities of traffic—40 percent or more in some cases. The platform’s 1.4 billion users–“an increasingly fragmented audience glued to smartphones,” as the New York Times says—consumes disaggregated news, practically agnostic as to source.

The disadvantage of consuming news and other external content via links, of course, is that sites take time to load, and can come cluttered with unsought content (including ads), especially for readers using smartphones. Facebook has said that it wants to make the online experience more “seamless”—and indeed, hosting written content might just be the logical next step to encouraging content producers to host videos inside Facebook (rather than on YouTube), by having those videos play automatically in news feeds.

But there’s much more to this than a more pleasing experience for Facebook members.

In return for offering up content, publishers will receive a share of the revenue from ads Facebook will run against it—even as the publishers’ own ads are stripped out.

This might be a big win for brands, as Facebook can mine a richer seam of user data than any traditional publisher, enabling more relevant and targeted campaigns. Is it a win for publishers?

Certainly the model makes compelling sense for a content producer like Buzzfeed, which exploits disaggregation by relying on native advertising. Buzzfeed and the brands that support it don’t care who hosts the content; they care about reach—something Facebook can supply in spades.

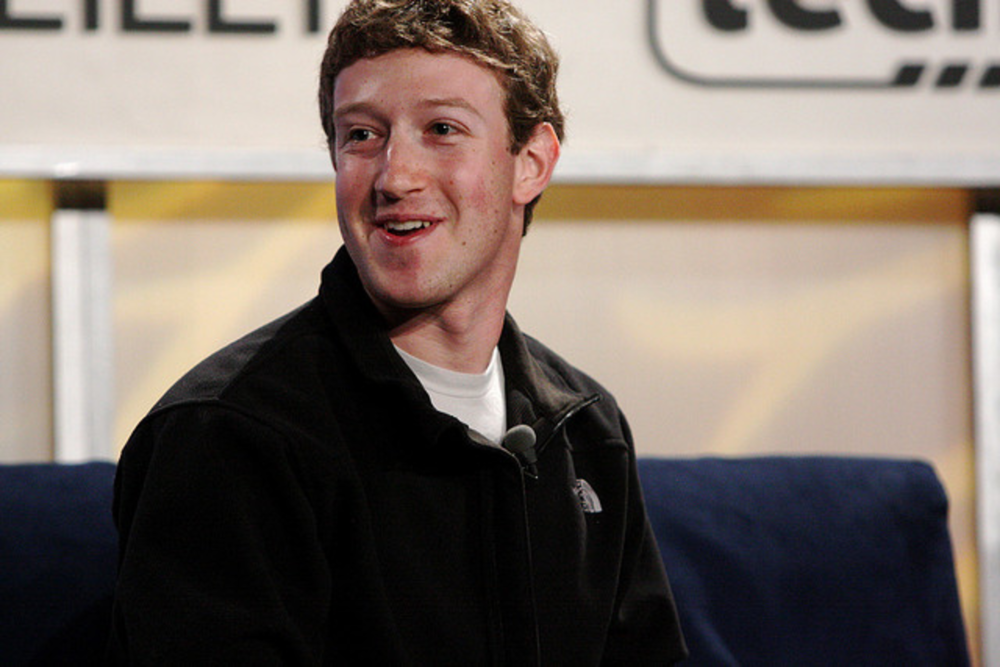

For traditional media, the stakes are higher. The New York Times has a base of subscribers, the core of which may be unlikely to abandon the aggregated product with which they’re familiar. But any news or other publisher that continues to monetize through banner, display and other advertising on its own site now has to consider a deal with—well, if not the devil, Mark Zuckerberg: Let Facebook publish their content, and advertise around it—or risk downgrading that vital lifeline of social traffic.

And while Twitter is currently constrained from becoming a full-fledged content host, through its self-imposed character limit, it’s certainly not impossible to imagine Google search pages hosting content rather than links under similar arrangements.

Traditional media mavens are duly exercised about the prospect of social media owning the news. (Of course this isn’t just about the news—see National Geographic). Some acknowledge, however, that the writing may be on the wall in any case for the old model of aggregating content on a proprietary website, monetized through subscriptions and advertising.

Where does that leave the kind of agile, cross-channel digital marketing that has come to be seen as vital for brands and publishers?

Marketing Beyond the Multi-Channel

Will Oremus at Slate has been vocal in warning about the implications of Facebook’s strategy. In January, he explained how Facebook’s preferential treatment of videos hosted inside the platform degraded video publishers to video producers, undercutting the lucrative potential of driving ads against videos on the publishers’ own sites. This week he pointed out that Facebook’s algorithms could “downgrade posts that link out to third-party websites. Ultimately, links may become all but obsolete in the Facebook news feed—much as YouTube videos already are.”

Look ahead five years, maybe just two years, and imagine an environment in which the trickle of major publishers converting themselves into content producers for Facebook–maybe Google and a freshly configured Twitter, too—has become a flood. Social media no longer drives traffic to content: it hosts content, publishes ads around it, and shares just enough of the revenue to keep the content wheels churning.

If that seems far-fetched, reflect on this thought from Mat Yurow (associate director of audience development at the New York Times, but writing in a personal capacity): “This is the publishing industry’s iTunes moment—and we’re blowing it.”

Suddenly, the multiple-channel online environment has shrunk to a handful of dominant channels. What need, then, for brands to identify audiences, build campaigns, buy space, and automate messaging across a bewildering range of web, mobile, wearable, and IoT media? I guess we’ll still have billboards, of course.

The risk of Facebook devouring the news has been widely discussed since this story broke. But why isn’t the social empire also well-positioned to take the reins of content marketing across the board?

Facebook already maintains a fairly tight list of preferred advertising providers. Last year, Facebook acquired ad tech company Live Rail. At F8, the announcement came that Live Rail’s capabilities would be extended from web video to mobile video and display advertising. If management of direct buys to Facebook moves inhouse, content marketing will be taken out of the hands of publishers too.

Living on Snacks

Some digital marketers, however, don’t believe that Facebook will be in a position any time soon to host much more than snackable short-form content. Alex Lirtsman, chief strategist at New York digital agency Ready Set Rocket, points out that content created for Facebook is different from the content publishers host on their own channels—and will remain different, least until there’s a significant change in the consumption behavior of Facebook users.

Facebook content is “much shorter and meant to be shareable,” he told me. Other channels create opportunities not only to tell a more detailed story, but also for further engagement—whether by clicking to other stories or subscribing. And with the details of Facebook revenue sharing still unclear, publishers’ own channels do remain 100 percent monetizable.

As for creating a more seamless experience for users, Lirtsman feels that “most publishers have done at least a decent enough job adapting to mobile, especially with video.” Just as he’s recommending clients continue to post videos to YouTube–“the world’s second-largest search engine”—he’ll also tell brands that, from a strategy perspective, Facebook is not a substitute for other channels.

Perhaps so. But it’s also possible, in a world that gives birth to 400 million Snapchat snaps a day, that people can live on snacks alone.